What goal would provide you with sufficient motivation to travel several hundred miles into unknown territory on foot, without the luxury of well-marked roads or motels and restaurants at predictable intervals along the way?

In 1859, the prospect of cheap, unclaimed land inspired two young European immigrants—Charles Rogler and his new friend Henry Brandley—to undertake just such a journey from Iowa to Kansas Territory.

Their adventurous trek of three to four hundred miles took them over rutted military roads and primitive trails; across rivers and creeks; onto rugged uplands; through the border region where proslavery and antislavery sentiments still flared unpredictably into violence; and into the shrinking territory of the beleaguered People of the South Wind, the Kansa tribe in whose honor, ironically, the Territory from which they were being evicted was named.

A century-and-a-half later, we have very little context for Rogler and Brandley’s achievement. Perhaps it is as difficult for most of us to conceive of walking that far as it would have been for 23-year-old Charles and 20-year-old Henry to imagine that one day their great- great-grandchildren could eat an early breakfast in Council Bluffs and arrive in time for lunch at the Hitchin Post in Matfield Green before heading out to enjoy a symphony in a pasture west of Bazaar.

For Charles Rogler, the foot-wearying miles from southwestern Iowa to the spot in the Flint Hills where he eventually staked his claim represented the last leg of a much longer journey that began on another continent, near the predominantly German town of Asch in western Bohemia.

As he neared the age of compulsory military service, his parents announced their intention to send 16-year-old Charles across the ocean to find a new home for the extended family, a common practice of the era that had little to do with what sort of future a lad might envision for himself.

By the time he decided to walk to Kansas Territory from Iowa—likely enticed by brochures proclaiming the glories of rich land, abundant water and balmy climate—he had already traveled nearly 5,000 miles and been parted from his family for six years. Walking several hundred more miles to chase another dream might have seemed to Charles by then a minor gamble well worth the taking, a pleasant diversion by comparison with, for example, skinning cattle in a stinking tannery on the shore of Lake Erie.

When they arrived here, Kansas was still two years shy of statehood and Cottonwood Falls contained only a couple rough cabins. The largest settlement in the area was the town of Bazaar, with six occupied houses. As the young men continued following the South Fork of the Cottonwood River, Charles finally spied the embodiment of his longings, an appealing plot of land that would become his obsession.

While investigating the location’s numerous attributes—at the confluence of a river and a creek; a mix of rich bottomland prairie he envisioned breaking out for crops and timber for building and fuel; and in the protective shadow of a substantial limestone bluff to the west with miles of open prairie for summer livestock pasturage—Charles may well have been composing a message in his head, a letter so grossly overdue that his family in Europe feared he had died.

What Charles could not have imagined at that hopeful juncture was how many intimidating challenges lay not far in his future.

Less than a year later, his extended family joined him on the claim, arriving in the midst of a drought so severe that rivers went dry and by late summer, pleas for assistance were broadcast nationwide from “Starving Kansas” and “The Land of Famine.”

Rogler descendants still tell the story of how the rest of the clan arrived in the early spring with a supply of precious flour that incrementally disappeared as visitors dropped by one at a time to welcome the newcomers and “oh, by the way, if you can spare it, could we borrow just enough flour for a pan of biscuits?”

At some point in the early years—perhaps after a band of proslavery guerillas rousted Rogler from his bed in the middle of the night for questioning—family legend claims he would gladly have handed over lock, stock and empty flour barrel for $300 if only some hapless traveler along the trail that is now the Flint Hills Scenic Byway had taken his hand-lettered sign seriously.

Instead, Charles stayed and doggedly tamed his patch of prairie into an increasingly neat and functional farmstead. In due time he replaced cruder structures with a hand-hewn walnut-timber barn and a fine house constructed of milled lumber hauled 150 miles from Leavenworth. He took advantage of an 1867 dollar-a-rod bounty law to define his claim with native limestone walls that still stand.

In 1869, Charles came relatively late to matrimony with a much younger woman whose secret dream of becoming an opera singer would suffocate under the accumulating burdens of marriage and motherhood in the isolated, wind-pummeled, grasshopper-plagued hills. Just nine years into the marriage, Mary Satchell Rogler was “duly and legally declared and adjudged to be insane” during the first of many stays in the newly-opened State hospital in Topeka.

Charles, meanwhile, carried on stoically in pursuit of his lofty ambitions. Thanks to a successful combination of thrift, ingenuity, human labor and old-fashioned horse power, he steadily expanded his 160-acre homestead into a diverse 1,800-acre farm that supplied virtually all of the family’s needs.

In 1888, not quite three decades after arriving on foot as an optimistic young pioneer, 52-year-old Charles died of pneumonia quite unexpectedly after getting caught out in a severe March storm. He left behind two sons and three daughters, ages 9 to 17.

How many times over the years had the memory of that first long walk to Chase County served as a model of perseverance for Charles Rogler as he grappled with the challenges of life on the prairie? How many times—after a crop-killing hail storm, a discouraging drought or another bout of illness in the family—did he recollect the simple virtues of continuing to put one foot in front of the other until the next destination came into sight? And how much of that ethic transmitted itself to the next generation?

Providentially, in that same spirit Charles’ youngest sister Adeline chose to defer her teaching career in order to help raise her nephew and nieces still at home, since their mother was institutionalized at the time of her husband’s death and would eventually die in the State hospital in 1915. His oldest son Albert also gave up pursuing his own formal education—a significant sacrifice for a young man with a deep love of learning—and came home from school in Lawrence to manage the crops and livestock . His old friend Henry Brandley stepped in to manage business affairs.

Less than twenty years after Charles Rogler’s death, the pioneer heyday came to an end as many of the once-hopeful homesteaders and speculators admitted to the bitter reality that a 160-acre farm on rocky ground was not the Garden of Eden they’d been promised by promoters.

From 1860 to 1900, Chase County swelled, thrummed and bustled with optimistic enterprises, but less than a century after Rogler’s arrival, the area’s dwindling population once again met the definition of a frontier, with fewer than 7 persons per square mile. The main share of his own grandchildren—born long after his death—would be among Chase County’s most notable exports: only three of fourteen would remain here to make their living from the land.

The Roglers who stayed and a fair number of others, however—shrewdly observing how readily the native tallgrass prairie lent itself to stock-raising—became the successful farmer-stockmen of the Flint Hills. By contrast to an ever-increasing roster of absentee landowners, the families who dug in their heels and stayed, who lived upon and loved the land, formed the vital backbone of their communities.

Henry Rogler, after graduating from the Kansas State Agricultural College in Manhattan in 1898, set to stamping his own unique brand on the Rogler legacy. In this sixty- some year endeavor, he was ably aided by another first-generation child of Chase County pioneers, Maud Sauble, who staunchly refused to marry Henry until she had also graduated from K-State in 1901.

Henry and Maud had in common the premature loss of their pioneer fathers to weather-related tragedies. Maud’s father David Sauble staked a claim in the county the same year as Charles Rogler, having left Maryland on his Morgan horse several years earlier when “the urge to go west struck him.” He died as colorfully as he lived—at the reins of a buckboard wagon—struck down at the age of 56 by a bolt of lightning.

The Saubles, too, had their claim to fame for walking: Maud’s mother Susan, according to family legend, laced up her boots at the age of 16 and walked close to 900 miles from Michigan to live with a sister in Chase County rather than put up with her tiresome stepmother any longer.

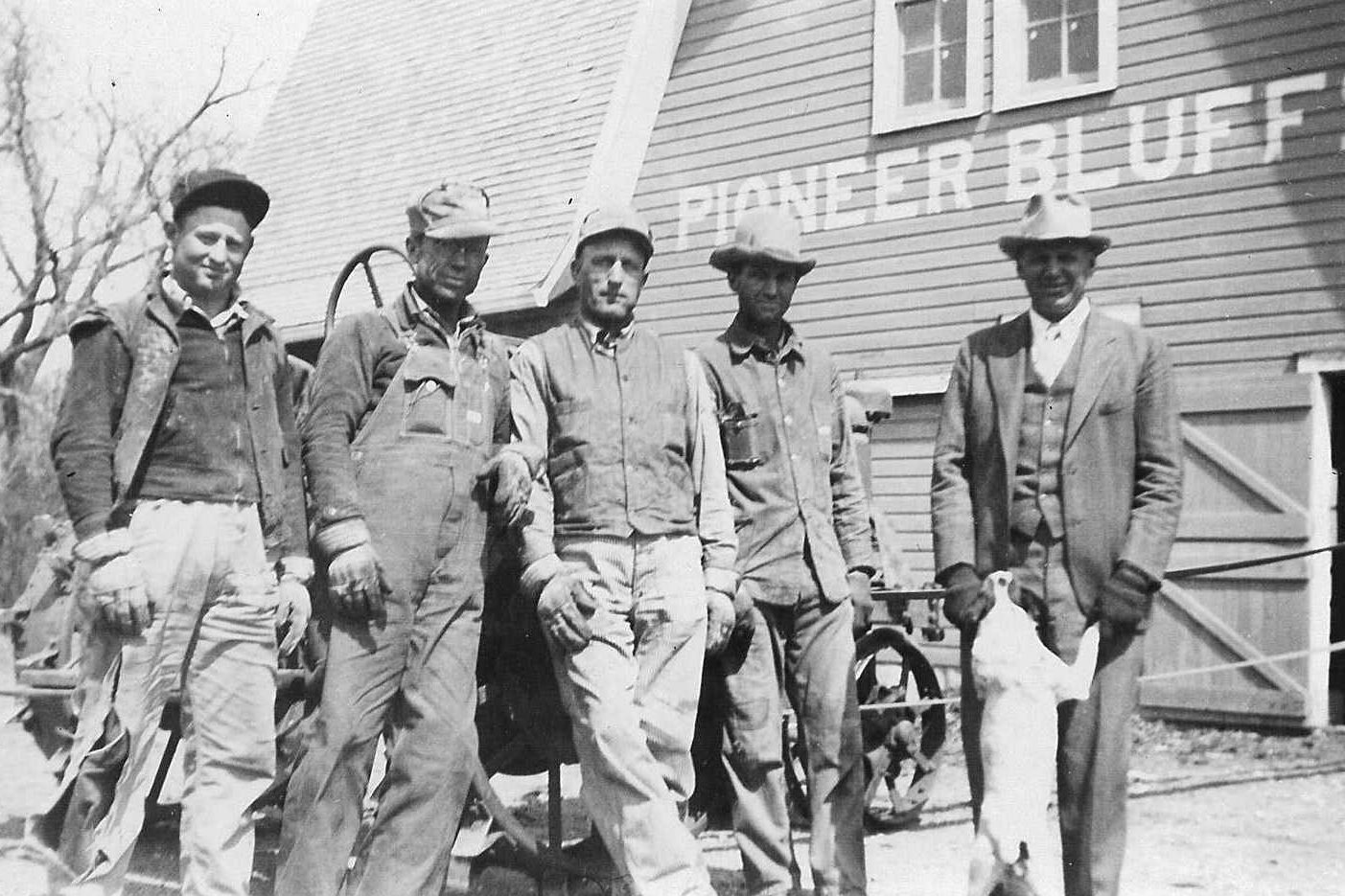

Is it any wonder, then, that when Henry and Maud were casting about for a suitable name for the family homestead, they chose “Pioneer Bluffs” to honor the courageous spirit and determination of their predecessors?

Under that next generation’s care, the buildings and grounds of the original homestead took on the tidy, pastoral look that is still appreciated by travelers on the Flint Hills Scenic Byway today. In 1908, Maud earmarked her private inheritance for the house of her dreams, a sturdy but elegant four-square that was the envy of the neighbors, chiefly because it was one of two houses in the area with running water. In 1916, they added a spacious barn and a combination granary & carriage house.

When their oldest son Wayne—the only one of their four children to stay in the county—entered the cattle business after graduating from K-State in 1926, he started out handling cattle for other people while building up his own herd, fulfilling a lifelong dream of being a cowboy. Unfortunately, economic depression and drought hit just as he was getting a toehold, calling to mind the stories he’d heard of his grandfather’s start in Chase County.

According to Wayne, it took all of the “ingenuity, frugality and perseverance” he’d inherited in order to ride out the downturn, but ride it out he did, becoming one of the most revered and influential cattlemen in the Flint Hills.

As cattle became the primary focus of operations and the Roglers expanded not only the quantity of land they owned, but the amount of grass they leased for grazing, their operation made the subtle transition from a farm to a ranch. During the same period, tractors, cars and trucks gradually began crowding out horses, mules and trains.

At the apex of Wayne’s career, the Rogler Ranch was one of the best known in the region, with an operation that encompassed some 60,000 acres, including leased pastureland, and managed 15,000 head of cattle a year.

Exactly one hundred years after Charles Roger walked into Chase County in 1859, his great-granddaughter Mary Ann, the only Rogler of that generation born in the county and the only descendant remotely likely to carry on the family tradition, graduated from K-State. Tragically, just six years later, Mary Ann Rogler died, foreshadowing the end of an era.

Henry and Maud died within two months of one another in 1972, Wayne in 1993 and his second wife Elizabeth in 2004. With no heirs interested in taking over the grass and cattle business, the land was divided into seven tracts and sold at auction in 2006 for $6.92 million.The 12-acre parcel containing the heart of Charles Rogler’s original homestead and the iconic Pioneer Bluffs farmstead a mile north of Matfield Green was purchased in 2006 by a group interested in preserving, interpreting and expanding the legacy. Today, Pioneer Bluffs, a nonprofit organization, offers visitors the chance to participate in the spirit of Flint Hills ranching through educational and experiential programs.